Enhancing Your Supplier Verification Process

By: Anne-Liese Heinichen

With the release of DFARS 252.246.7008, supplier qualification requirements remain front and center in the US Government’s efforts to prevent counterfeit parts from entering the military supply chain. Of importance, not only to government contractors, is the topic of supplier assessment as a key element in every organization’s documented mitigation program/control plan.

While sourcing from the original component manufacturer or an authorized supplier should be specified whenever possible, the reality is that organizations are sometimes left with few options and are forced to seek alternate sources of supply, increasing the risk of a counterfeit encounter.

One of the responses we have seen at ERAI is the inclusion of statements in purchase order documents stating that, “no parts from China will be accepted” or that organizations will not procure from suppliers that have purchased parts from China. But provenance for a part is many times difficult and/or impossible to obtain directly back to the OCM if purchasing from outside of the authorized distribution channels.

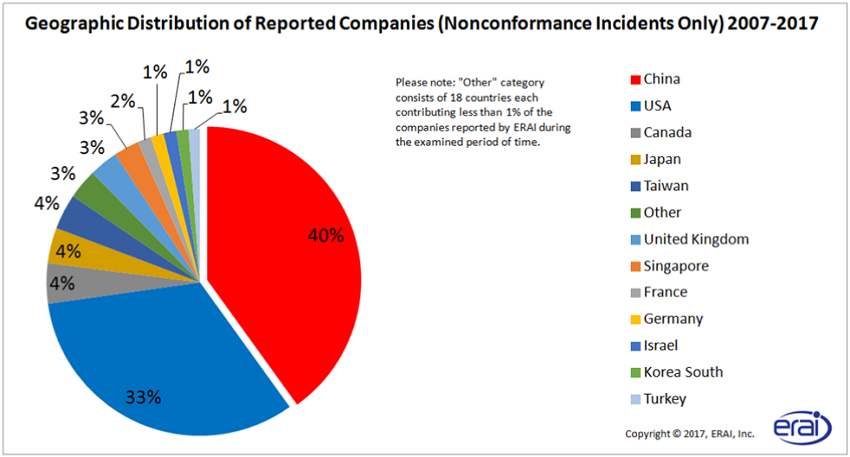

When looking at ERAI alert statistics from 2007 through the third quarter of 2017, specifically at organizations that have been identified as the supplier of nonconforming parts, we see that the majority of suppliers are located in China (40%); 33% were located in the USA and the balance (27%) in different countries around the world, showing that a policy of not purchasing from Chinese suppliers alone is not a sufficient policy.

The inclusion of such language, although helpful, is not an adequate substitute for sourcing parts outside of your organization’s approved vendor/supplier list. Qualification of a supplier should ensure that the organization has implemented its own documented counterfeit mitigation program and maintains its own approved vendor list.

Common industry best practices cite requirements such as audits (on-site preferable), adherence to industry standards, quality certifications (which should always be validated), documented warranties and return policies, personnel certifications and training, documented purchasing and acceptance processes, trade references, performance history, and any recorded problems reported by industry data sources (e.g. ERAI and GIDEP). However, there are additional simple steps that organizations can take to enhance their supplier selection process.

Along with our public website (www.erai.com), ERAI maintains an internal proprietary database containing profiles of over 28,000 organizations that either purchase, sell, and/or integrate electronic parts and/or provide additional services to the industry. The profiles include addresses, individuals and their contact information, banking details, relationships to other organizations and references, when available.

As part of ERAI’s data collection process, we verify corporate registration (state, provincial, or federal); tax documentation; whether or not an organization has a CAGE code and addresses and contacts provided therein; searches for individuals and corporations on the US Consolidated Screening List; when and by whom a website domain was registered; and social media accounts. When focusing on an organization’s address, we use resources such as Google maps to initially determine if the address is legitimate or if the organization is using a virtual office space or mailbox facility (e.g. UPS Store). We may even go further to investigate who owns the property and for how long. Even simply “Googling” an organization, address, contacts and phone numbers can yield surprising results.

A recent example highlights how ERAI’s processes can be applied in your organization’s documented counterfeit mitigation program to identify supplier risk. An individual sought to subscribe her distribution company to ERAI’s services. The individual referenced her company’s website which featured UK phone and fax numbers, no company address, an ISO 9001 logo, and a statement that the organization was an “ISO9001-2008 certified company”.

ERAI requested a copy of the ISO 9001 certificate to which the individual responded that her company was “in process now” and when pressed, admitted that her organization was not certified.

Verification on the United Kingdom’s Companies House website showed the company was registered in 2012. A search of the registered office address in Google maps revealed the address appears to be a residence in a Welsh town. A Google search of this address produced Companies House data showing that a total of 222 companies are registered at this same address. Through cross-checks in our proprietary internal database, we uncovered five other industry-related organizations that purport to be located at the same Welsh address. ERAI has submitted an inquiry to the Welsh Coordinator of Companies House asking if or how registered addresses are verified but, to date, no response has been received.

The registered director is a Chinese national with an address in mainland China. An ERAI membership application was completed and returned providing the name of ten customers, located in Germany, Hungary, Turkey, Austria, Spain, Netherlands, South Korea, and China, as references. It is unknown whether those organizations are aware that the distributor is operating from mainland China.

Organizations are encouraged to follow the same processes as those in place at ERAI and perform verifications from all available data sources. Additionally, organizations should be proactively sharing their experiences with other organizations so that they too can use this data to identify risks before a financial loss or a counterfeit part enters their facility. The reality is that risk mitigation is a team sport, and every one of you is an important part of this team.

ERAI encourages members to contact our office for assistance with the supplier verification process. Prior to sustaining a loss or receiving counterfeit goods, if you receive a suspicious email or if you need tips on locating information publicly available on the Internet, let us know. Many times, even small insignificant details can be valuable data. Contact our office at 239-261-6268 or eraiinfo@erai.com with any inquiries.

ERAI Members: Did you know?

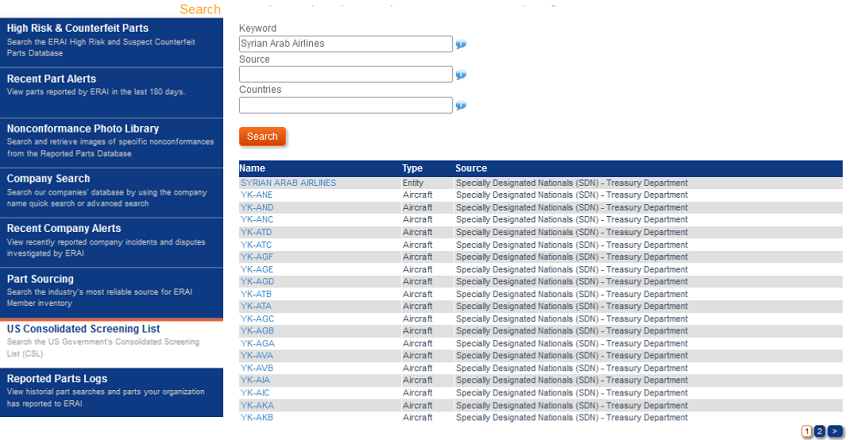

Under the ERAI search tab, Members can search the US Government’s Consolidated Screening List. Per the Bureau of Industry and Security, "the CSL is a streamlined collection of nine different "screening lists" from the U.S. Departments of Commerce, State, and the Treasury that contain names of individuals and companies with whom a U.S. company may not be allowed to do business due to U.S. export regulations, sanctions, or other restrictions. If a company or individual appears on the list, U.S. firms must do further research into the individual or company in accordance with the administering agency’s rules before doing business with them."